Acknowledgement

It is customary for this

particular section to be written at the end of an article. But in

this instance, I wish to make it quite clear from the start, that it

is only with the encouragement and permission of Hugh Boyd that I am

able to complete this document. Hugh is the first author, with

Jeffery Harrison and Allan Allison, of 'Duck Wings - A Study of Duck

Production'. This supremely useful book was published in 1975 (as a

WAGBI Conservation Publication in co-operation with the Wetlands

Trust) so it has long been out of print and copies are hard to find.

What follows is therefore a summary of the most important and

salient points from this book interspersed with my own personal

experiences and practical advice.

Introduction

Picture the scene. You've

had a successful days wildfowling and you sit down to write up a

brief resume of the dayís events in your diary. The usual details

are included - weather, state of the tide, the location you chose,

maybe a brief line about the flora and fauna you noticed in addition

to the wildfowl. Almost certainly you'll note down the number of

shots you fired as well as specific details about the cartridges you

used and how they performed. But above all, you will record the

species of duck you bag and perhaps their sex.

However, before you close

the book and sit back to enjoy a glass of your favourite tipple,

there remains another piece of information that you can add to the

rich tapestry of material you collect. With practice and experience,

by careful examination of the size, shape and colour of wings

feathers, you can almost always accurately determine the age of

ducks. By that I mean either a Juvenile/First Winter bird or an

Adult.

For you as an individual

this may become another interesting facet to the sport of

wildfowling. Yet when collated at a national level, the resulting

information can prove very useful and beneficial to wildfowl

conservation. It may be used to determine the abundance of each

species, the percentages of duck and drakes and in particular the

proportion of young to adult birds. This ratio is used to understand

breeding success and mortality rates which together act as a measure

of each season productivity. While the BASC maintains a limited

study, it is in the US that the analysis of duck wings is undertaken

on a massive scale. Each season for the last 40 years, up to 100,000

duck wings are examined at 'wingbees' across the flyways and the

resulting data forms an integral part of setting and evaluating

hunting seasons.

Collection and

Preservation

First off, shoot a duck! It

is possible to examine wings while still attached to the bird,

especially if the features are clear cut, but in most cases

manipulation is best achieved by removing them. It is vital that

they are kept in the best possible condition since in some cases you

may be looking for quite subtle feather differences. To this end,

avoid stuffing birds into a game bag or at least ensure that you

smooth the wings against the body before carefully packing away.

For obvious reasons

endeavour to pick the best wing from each bird. If both are badly

smashed or particularly muddy, you are better off discarding them

rather than risk making an incorrect judgement. By all means have a

go, but be very cautious about your conclusions.

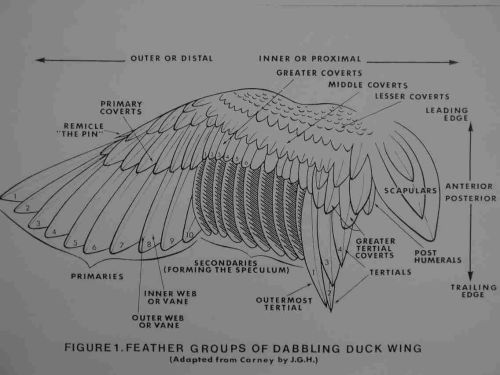

Try and cut the wing off

neatly at the shoulder (kitchen scissors are very effective) and if

possible try and take the fold of skin to which the scapulars are

attached (see Figure 1). Inevitably some wings will be wet,

bloodstained and muddy, the later being the most problematic and

unfortunately not uncommon problem when shooting in an estuary. So

once removed, they should be air dried as soon as possible. This is

very important because feather shape can be altered in appearance

when it is wet. One word of caution, I have found it's best not to

place them on a radiator as the consequences of forgetting you've

done so can be quite aromatic. When dry, soiling can sometimes be

removed using a soft brush making sure you sweep with the lye of the

feathers. Remember though, wings and feathers may be quite tough and

resilient, but keep handling to a minimum to avoid disrupting

important features

If you are not going to

examine or 'read' the wing immediately, the most convenient form of

preservation is freezing. Simply pop it into freezer bag, make sure

you label it (date, species and sex), and find somewhere in the

depths of your freezer that the wife won't object to you using. In

this state it is possible to store wings indefinitely and if you

collect your best examples for each species, you'll soon have a

useful reference collection. Alternatively, you can take photographs

and if you have a digital camera and PC store the images in your own

virtual gallery but you'll need to take good quality close ups for

this to be effective.

Figure 1 Feather Groups

of Duck Wing

Sequence of Plumage

change

Close study of feather

changes between Juveniles and Adults over many years has ensured

that for most species the exact sequence is known and can be used to

determine age. Juveniles, be they duck or drake, have plumage

markings broadly similar to adult females of the species. Often the

only clear differences are that juveniles have less defined markings

and appear slightly duller. Once fledged the young ducks will

undergo a moult into their first winter plumage.

It is not possible to give a

precise timing for this moult, other than to say it will occur some

time between September and January. This is due to variables such as

the date of hatching, environmental conditions and the physical

condition of each bird. For this reason it is likely you'll see all

stages of the moult sequence throughout the course of a typical

wildfowling season.

Fortunately though, the

majority of juvenile wing feathers are retained until the bird is

around one year old. Which means that although it will have

undergone a full body moult in this time, it should still be

possible to tell it apart from adult birds (more than one year old).

Perhaps the single most

important fact to remember is that the presence of just one of these

juvenile feathers is enough evidence that the bird is not yet adult.

So once you found one, you need not examine any more, save for your

own interest.

Moult Sequence from

Juvenile to First Winter

Primaries Not Moulted

Secondaries

(speculum) Not Moulted

Primary

Coverts Not Moulted

Lesser

Coverts Not Moulted

Middle

Coverts Not Moulted

Greater

Coverts Not Moulted

Tertials

Moulted

Greater Tertial Coverts

Moulted

Post Humerals

Moulted

Scapulars Moulted

There are two important

caveats to this sequence of events. Firstly, if feathers are damaged

and then lost from the wing they may be replaced by feathers of the

next sequence ie adult. So it is possible to see adult features that

should not have normally moulted on a duck that is very clearly

Juvenile/First winter. Secondly, the plumage of adult females that

have bred late may become badly worn and as you will see later,

feather wear can be indicative of juvenile birds.

Age Differentiation

The basis for the

examination is to follow a wing 'key' which describes wing features

and how they appear dependant upon age. So, with reference to Figure

1, simple work your way down the list checking for the specific

identifying characteristics. You will see that although most feather

groups are included in each key, they may not necessarily be listed

in the same order. This reflects those feathers that are the most

practical and give the most definitive diagnosis for each species.

While you may only need to refer to a few of these when examining

early season birds, as winter progresses and new feathers are grown

it will become increasingly necessary to examine all the listed

groups. If you are unsure if a listed feature is identical to the

one you see, move onto the next one. It is not necessary to get a

perfect match for them all, one 'hit' of a juvenile feather is

diagnostic.

Drake Wigeon

By far the easiest duck to

age is the cock Wigeon, which can be readily identified by a single

feature. For the sake of completeness though, the whole key is

included together with images of Adult and First Winter birds (see

Images 1 and 2).

|

1. LESSER AND

MIDDLE COVERTS

|

|

|

a. Brownish-grey with

dusky barring and narrow buff edge to posterior rows of middle

coverts

|

Juvenile/First Winter |

|

b. Greyish-white with

dusky margins and barring

|

Juvenile/First Winter |

|

c. Brownish-grey with

newly moulted white feathers (rare)

|

First Winter |

|

d. White; anterior

lesser coverts forming grey, sometimes vermiculated leading edge

to wing |

Adult

*** |

|

|

|

|

2. GREATER COVERTS

|

|

|

a. Greyish-brown with

darker sub-terminal and white terminal bar

|

Juvenile |

|

b. Dirty white with dull

black sub-terminal bar

|

First Winter |

|

c. White, with black

terminal bar |

Adult |

|

|

|

|

3. SECONDARIES

(SPECULUM)

|

|

|

a. Anterior quarter

metallic green except on outer two/three feathers, remainder

dull black with narrow white trailing edge

|

Juvenile/First Winter |

|

b. Anterior half

metallic green, posterior half glossy black |

Adult |

|

|

|

|

4. TERTIALS

|

|

|

a. Short, dark brown

with darker outer vane and narrow white and frayed outer margin.

Broad greyish-white band on outer vane of first tertial

|

Juvenile/First Winter |

|

b. Long, lanceolate and

pointed, outer vane black with well defined smooth white margin,

inner vane grey, shaft white. Broad white band on outer vane of

first tertial

|

Adult |

|

5. SCAPULARS

|

|

|

a. Dark brown with paler

margins

|

Juvenile |

|

b.Vermiculated, grey and

white |

Adult |

|

|

|

|

6. GREATER

TERTIAL COVERTS

|

|

|

a. Brown, with pale

frayed margin

|

Juvenile/First Winter |

|

b. Grey, with white

smooth margin |

Adult |

***

The fully white shoulder

(lesser and middle coverts) of the adult is usually obtained during

the first summer moult. So if present, this is sufficient evidence

to classify any drake Wigeon. It has been noted however that the

coverts of Juvenile/First Winter birds can become whiter during the

season as a result of colour change without moult. But never to the

extent that they could be confused with the bright white coverts of

an adult.

Image 1 Adult Drake

Wigeon

Image 2 First Winter

Drake Wigeon

Discussion

Although the images have

been degraded to reduce file size, the differences between some of

the feather groups are still clearly visible. The white shoulder of

the adult with its grey leading edge contrasts strikingly with that

of the juvenile (part 1 of key) which is why this single feature is

so useful in distinguishing the two. You can also see the reduced

amount of metallic green present on the speculum of the juvenile

compared to the adult (part 3 of key). Finally, though itís not so

clear, compare the tertials of the juvenile and adult. You will

hopefully see that the tertials of the younger bird are not black

and have a narrow white and frayed outer margin (part 4 of key).

|