|

Photo by Dale Tolmsoff

American

dog sports for retrieving breeds have a relationship to actual

fieldwork that is sometimes less than obvious, and that is

the focus here. It doesn’t require much imagination to understand

that hunting dogs get better with experience on game birds, and

these events are a vehicle to accomplishing that. But there is much

more. Like the UK trials, American dog sports promote competition,

and that tends to elevate standards. Field Trials provide

competition in a dog vs. dog venue, while Hunt Tests offer a ‘dog

vs. an established standard’ platform for testing.

The intent of this commentary is to

provide a brief history of the events, and what will hopefully be a

useful insight into these pursuits. It’s significant to note that

even in the U.S. there is a great deal about Field Trials, and even

Hunt Tests, that many casual observers have difficulty

understanding.

In the beginning

The

history of American Field Trials, as events governed by the American

Kennel Club, dates back to the 1930’s. Prior to that there were

trials held according to traditional British rules, with the

fortunes of the Retriever breeds in America, and the Labrador in

particular, being tied to the fortunes of wealthy, Eastern estate

owners who, being accustomed to shooting in Scotland, began to

import Labs from the British Isles in the late 1920s and early

1930s.

The first Labrador Retriever was

registered with the AKC in 1917. Not only has the Labrador become

the most popular breed in America, the Lab clearly dominates the

retriever gun dog sports here, as well. The loveable Lab is welcomed

in many ways in U.S. households, with 165,970 of them being

registered with the AKC in 2001, ranking them well ahead of any

other breed of any type.

Still, American Field Champions have

been crowned in other breeds over the years. Goldens, Chesapeakes,

and even Flat Coated Retrievers have earned those titles. The same

is true of Hunt Test titles, such as MH (Master Hunter).

There are several organizations that

sanction Hunt Tests, each with its own distinctive style. The

objectives are sufficiently alike that I will forgo listing the

rules for each. Instead, I would like to offer a descriptive

commentary on the events in order to promote a better understanding

of them for those who have not had the opportunity of seeing them.

The end result in both events (hunt

tests and field trials) is the revealing of core attributes in dogs

for selective breeding, while providing an enjoyable pursuit for dog

enthusiasts.

Field Trials, the least understood

of American dog sports

1931 saw the organization of the

Labrador Retriever Club, which put on the first field trial for

Retrievers in America on an eight thousand acre estate in Chester,

New York-deliberately holding it on a Monday so that it would not

attract a gallery. The event of that day, and of this are separated

by far more than an expanse of time!

There is a provision in the AKC rulebook

for retriever field trials that, while it has been present for

decades, has become purely ornamental: Under Basic Principles,

“1.

The purpose of a Non-Slip Retriever trial is to determine the

relative merits of Retrievers in the field. Retriever field trials

should, therefore, simulate as nearly as possible the conditions met

in an ordinary day's shoot.”

While

U.S. trials continue to provide evidence of “the relative merits” of

Retrievers in the field, the only way in which the “conditions met

in an ordinary day's shoot” are observed is with regard to the very

difficult natural terrain in which they are conducted, along with

the retrieval of game birds; principally ducks and pheasant.

The

cosmetic appearance of today’s Field Trials is a two-edged sword.

While they are the vehicles that allow the conducting of uniform

tests with uniform objectives, they are of such a contrived

appearance that the casual observer is left scratching his/her head,

and wondering, “what on earth does this have to do with

hunting dogs?” Opinions vary.

These

events have come to test isolated attributes in working retrievers

to the extent that they have an almost clinical appearance, even in

the beautiful wild areas in which they are conducted. The

clinical-type dynamics, and the diverse natural environment have

become a team of logistical bedfellows. Because the nature of the

event has evolved, both are necessary.

The degree of difficulty in the tests

for these events has swelled exponentially, creating the need for a

more contrived looking set up, while consideration for the dog has

necessarily remained. The variation in cover and terrain, along with

the need for certain types of water, shoreline, and combinations of

all of these, must exist to test the core attributes of working

retrievers, insomuch as that may be done uniformly. It is, indeed,

the testing of those core attributes that has become the central

focus of the dynamics of today’s trials.

It has long been recognized that

distance has the effect of making all retriever work more difficult,

so exceptional distance has become the hallmark of many tests in

American Field Trials. It causes the erosion of control by a

handler, and exacerbates the effects of all the diverting influences

that retrievers face in their work. That deserves some explanation.

Distance

Judges in trials must possess sufficient

dog knowledge to understand how dogs are influenced by certain

conditions. A marked retrieve at twenty yards on a surface as

featureless as a putting green should be a minimal challenge, even

to a puppy. Make that same mark two hundred yards and the challenge

is much greater. Add in cover, changing terrain, a crossing wind,

water, re-entries, and so forth, and you continue to up the ante.

On a blind retrieve the erosion of

control that occurs over extended distance is universally

understood. Therefore blinds, especially in the upper classes, can

be in excess of 400 yards, and can cover some amazing terrain.

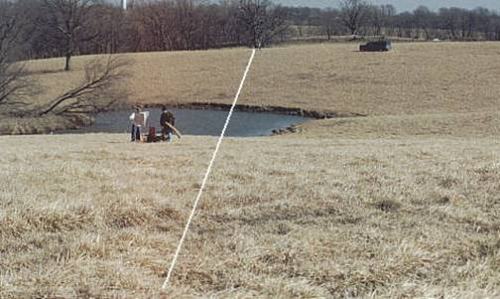

Just an example of typical Midwestern terrain.

Marks

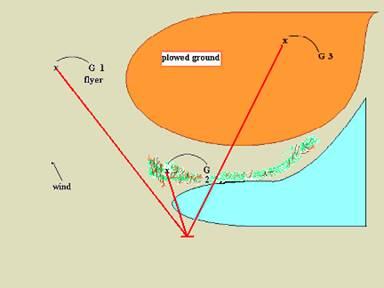

Here is an example of a fairly typical

all-age marking test.

“G” indicates a gunner/thrower in the

field. “X” denotes the area of the fall. This is what is known as an

indented triple mark. The center mark is a memory bird, and is made

difficult by being the ‘indent’ bird, along with several other

considerations.

It is the second bird thrown, following

the live shot flyer on the left. Then a long ‘control’ bird (dead

bird) is thrown on the right. The dog will cross water, drive

through a strip of dense cover, then across an open area, and out

across an expanse of ploughed ground to get his first mark. Upon

returning with that fall, his first memory mark is the

indent, which is often retired; the gun/thrower becomes hidden so as

not to provide a visual cue that would make the mark easier.

There are several natural tendencies in

dogs that make this particular mark difficult. First, it is a memory

mark. Then, it is placed so that a dog will tend to cheat both water

and cover en route to it, placing them on a potentially perilous

course toward the flyer on the left. If that fall is retrieved

second, it establishes a preconceived notion about the line to be

taken subsequently, and makes it even more difficult to succeed on

the indent.

What’s being tested in a set up like

this?

Let’s dissect this test to determine

what is actually being tested. First, what is being tested is pure

marking and memory. Bird placement and distance promote this.

Second, trainability coupled with a willingness to cooperate with

the handler. After all, from the perspective of most dogs, it would

be far more enticing to go for the flyer on the left second. Only

significant schooling (and trainability in the dog) are likely to

allow the dog to retrieve that very difficult ‘indent’ mark second.

The third quality tested here is

sagacity – a special type of intelligence in dogs that allows them

to problem solve in highly challenging circumstances, such as a test

like this one presents. Most dogs of hunting quality possess

intelligence, but only the best are sagacious enough to sort out a

test as fraught with challenges as this one with any consistency. In

the upper classes of today’s field trials, most dogs entered are

quite adept at this level of work, so the standards must be kept

high.

Blind Retrieves

Since a

blind retrieve is purely the result of training, control is the

focus of such tests in U.S. trials. Dogs are judged against each

other on the basis of comparative merit, so great emphasis is placed

on constructing tests that challenge control to very high degrees.

This is

just one example of how a simple pasture and stock pond can become a

viable test of control on a blind retrieve. This one is in the

set-up phase, which allows its components to be easily seen. The

close gun station is setting up to shoot a flyer mallard, while the

blind is being placed on the far hill (about 250 yards). The line to

this blind passes closely behind the gun station in order not to

miss the water altogether. The hill drops down slightly beyond the

gun station, so the handler will have to move up as the dog passes

the gunners to keep his/her dog in sight. The dogs did not want to

stay on line toward the far end of the pond, and many drove left

instead of straight up the far hill to the bird.

Less

direction given by the handler, coupled with stylish and accurate

responses from the dogs, will keep a dog well positioned in the

competition. Accuracy is a key feature, as it clearly demonstrates

trainability and willingness to take direction from the handler. In

order that these key traits are tested to a great enough extent to

demonstrate the best of the field of dogs, these tests are carefully

contrived with immensely challenging components.

Because

the level of competition has continued to rise, a trial is rarely

won with a good blind, but a poor one often loses them. Marking is

of primary importance. It is of primary importance because is

reflects most of the finest core attributes of a quality retriever,

and that is what provides selective breeders with a tangible

yardstick by which to continue to preserve and advance the retriever

breeds for future generations. Marking is one way in which genetics

are quantifiable.

The distinctions

between Hunt Tests and Field Trials

In the

late 1970’s a group of people, largely comprised of sporting dog

writers and retriever trainers, decided that retriever sports needed

to move in a different direction from the increasingly competitive,

and more artificial looking field trials of the U.S.A., and set out

to contrive a new game for the retriever enthusiast. Essentially,

the point of greatest agreement appears to have been restoring an

atmosphere in testing that conformed more to the ‘conditions met in

an average day’s shoot’. It was felt that there were portions of the

makeup of working retrievers that had disappeared as considerations

in field trial testing, and that this new sport may help to promote

them.

In

addition, there were aspects of competition that these organizers

were opposed to. Certainly more people would be apt to participate

if they weren’t faced with early elimination because their dogs

couldn’t perform well enough to be considered a potential winner. As

long as they can do the work prescribed by the sanctioning body as

being at a level appropriate for a dog in their class, a hunt test

dog has an opportunity to continue in the event to earn a qualifying

score toward a title at that level.

The

ribbons are all the same for most of these events because there are

no placements. A dog either meets the criteria for the class (in the

judge’s view), or fails outright. The perspectives remain somewhat

polarized between those who run hunt tests and those who compete in

field trials. Most field trial competitors appear to maintain that

the non-competitive venue erases the distinction of the better dogs

for the sake of selective breeding. One dog with a Master Hunter

title may have earned it in successive scores, for example, while

another required years, attending dozens of tests to barely eek out

enough scores to attain the same title, and neither had ever been

required to distinguish itself as being the better dog in any given

event or on any given day. To the hunt tester, it is enough that a

dog was able to work at that level successfully enough times to

acquire the necessary scores.

I view

the differences in testing as being largely a matter of cosmetics

and distance. A mark or blind retrieve of more than 300 yards would

be the exception rather than the rule in a hunt test in any of the

sanctioning organizations. Guns hidden vs. guns visible – and/or

retired, handlers and guns in white vs. handlers and guns in

camouflage – these represent the bulk of cosmetic differences

between the events. Of course the primary difference is that dogs in

field trials are competing to win, while hunt test dogs compete to

match a standard set by the organization sanctioning it.

If the

standard of performance rises in the hunt test venue, it will be the

result of consensus within a governing body, rather than anything

that occurs during a single event, like a field trial where someone

must be declared the winner; the best of the best that weekend.

Gun

stations in hunt tests are very rarely visible. Normally, the guns

are hidden, but may walk out from a ‘hide’ to shoot a diversion

mark, for example. Guns may also be visible for a ‘walk-up’ mark, as

well. They’re great fun, and the judging is often very creative due

to the effort being made to provide the look and feel of hunting

conditions, while essentially testing the same traits that are

tested in more clinical ways at field trials.

Photos by

Dale Tolmsoff

All

participants are required to dress in either camouflage or natural

colors. Often handlers carry guns, or mock guns. As in trials, game

birds are used, and many concepts in marking and blinds are also

used that are merely different looks at the same ones used in

trials.

In both

events, onlookers and newcomers are welcomed. In both cases, the

dogs are the central focus, with a majority of participants being

avid hunters.

|

|

|

Evan with

FC-AFC Trumarc's Too Hot to Handle ("Lucy") |

|

|

|

A Brief

Biography of Artist and Author Evan Graham

Evan Graham was

born November 6, 1946 in

Long Beach, Ca.. He is a retired

professional dog trainer, and ex-paramedic. He now works as

a Registered Nurse in a metropolitan hospital. He is married

and has four children and nine grandchildren. He is also a

columnist for The Retriever Journal, and has

trained and handled many dogs that earned positions on the

National Derby List, including five in a single year; one of

them being number three with seven wins. At least three of

the dogs he trained as a professional became Field

Champions. The driving force for his development of the

Smartwork method was the belief that one can

never know how good any dog is whose Basics were not

thorough. As a portion of method refinement, he maintained a

strong focus on efficient, effective Basics. |

|

Evan Graham

5020 N. Topping

Kansas City, Missouri 64119

USA

816-452-2335

EVANEvnG@aol.com

http://www.rushcreekpress.com/

|